“Women aren’t reporting sexual assault. I know why.”

8 March 2018

Trigger warning for rape.

There is a moment when the line is crossed. The line is invisible, but the moment is unforgettable. The moment we become survivors. The crossing is involuntary and as we are pushed over it, we lose something. An imperceptible layer of skin is stripped, and our bodies are suddenly alien, no longer our own.

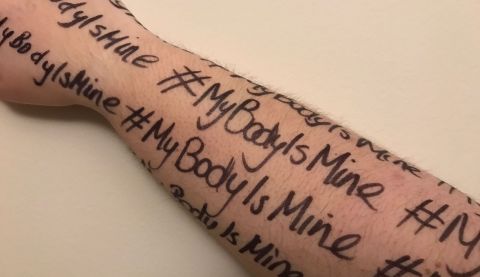

"My body was the one on trial.". Photo: ActionAid

Many years before I joined ActionAid, I found myself on the wrong side of that line, having lost my layer of skin, but having gained a new identity as a rape survivor. Like so many women that ActionAid works with, I had to start from scratch, remembering my body and reclaiming my control.

I look at these legs that carried me to work on autopilot the morning after. I taste the tip of the tongue that held the word ‘rape’ for a week before the teeth and lips made way for its release. I smooth my fingertips over the nails that were lost, nervously peeled away in the waiting room of a sexual health clinic.

I focus the eyes that held the steely gaze of the defence barrister as she asked me if my body had fought back. No, it hadn’t. Had it punched him? No. Kicked him? No. Bitten him? No. My hands, my feet, and my teeth had not come to my aid because they were afraid he might hurt them more.

The barrister looked perplexed and her next line of questioning implied that he had not given me any reason to think he would be violent towards me. I was equally perplexed – did rape no longer count as violence? Either way, my body had obviously not reacted the way it was “supposed to” react, and so my body was the one on trial, as is the case for many survivors who attempt to access justice for the crime perpetrated against their body.

My body had obviously not reacted the way it was 'supposed to' react, and so my body was the one on trial."

My mind has not forgotten the fresh trauma that arrived 18 months after I was pushed over the line. I had been working, working, working, to rebuild my body and yet, after one day of cross-examination, it shook so violently that I thought it might disintegrate. My voice had been ignored once again.

I had not screamed or shouted or kicked or fought against this barrage of questions, my body had been defeated, once again. A court clerk led me away to the witness room and paused. She turned to me and said, “It’s not personal.” She turned back and continued to walk. I continued to follow. I had no voice left to challenge.

What could I have said? Did I really need to explain how utterly personal it was? What could be more personal than my body being laid bare in front of a courtroom of strangers? Strangers regarding it with increasing suspicion as the barrister’s questions implied in every possible way that my body was a lying body, a criminal body, whose only reason for being there was to tarnish the reputation of an innocent man.

Why would my fellow survivors seek justice in a system that treats their bodies with such suspicion; a system that seems to be undecided about whether or not our bodies belong to us?

I had been working, working, working, to rebuild my body and yet, after one day of cross-examination, it shook so violently that I thought it might disintegrate."

This indecision is not confined to the legal system. 2,718 days after my assault, I stretch the muscles that still tense involuntarily at every unexpected scene of violence against a woman discovered in a book, a film or a TV show. I stretch because these muscles are weary from overtension. I try not to listen with these ears as the actors deliberate whether or not the woman deserved it; the same ears that often wish for selective deafness every time someone likens a trigger warning to censorship. Perhaps these ‘someones’ have not experienced that muscle tension when their body is jolted into a memory; when a reminder is thrown in front of them and they have no warning and no opportunity to look away.

I can only assume this tension is my body’s unconscious reaction when suddenly reminded of its previous alienation. My body is literally holding on to itself for dear life.

Why would my fellow survivors seek justice in a system that treats their bodies with such suspicion; a system that seems to be undecided about whether or not our bodies belong to us?"

For now, I must find relief in the company of those who are not indecisive about the ownership of a woman’s body. I flex the hands that have been grabbed by others, squeezed in support and love, at the end of the arms that have been pulled into hugs more times than I can remember. I think of the mind that has sunk into the pit of fear and despair but has then been coaxed out again into joy and happiness.

I smile at the women that we stand with in solidarity, knowing the courage it has taken them to stand up for their rights in the face of an overwhelming deficit of justice.

I use my voice to speak. Loud and proud.

My body is not the property of another.

My body is not a weapon of war.

My body is a roadmap of everything I have done and the strength it took to do it.

My body is mine.

Today, I’ll be spreading this message by writing #MyBodyIsMine on my body and sharing my selfie on social media. Join me, and together we can show our solidarity with survivors around the world.